We’re very grateful to Eugene F. Gray for transcribing several great accounts he discovered in old publications.

Sixth of September

This day, which commemorates an important event in the history of the American Revolution, has again come, and passed; and as a people, we have permitted it to pass “without note or comment.” True, the day of anniversary was the Holy Sabbath, and, therefore, the wonted devotions of Christian worshippers, might furnish a plea for permitting it to pass, without public notice. But then, when the anniversary has returned on other days, than the Sabbath, it has of late been marked, only by the same cold forgetfulness, and neglect.

And we confess, that we are pained by the reflection, that there seems stealing over the American heart, a spirit of indifference, and even forgetfulness, in relation to the events which were accessory to our National Freedom, which to us indicates anything but gratitude, in the hearts of the American people, to that Benignant Providence, which has made us as a nation, what we are.

We are not forgetful of the fact, that it may be said, that the indifference which marks the age, in reference to the struggles of the past, results from a greater enlightenment of the public mind—and the consequent advance of peace principles; and, therefore, is produced a disgust, and contempt, for war, and its doings— and, that it is therefore meet that we should permit all traces of war, that now exist, and all knowledge of the day when our nation has been called to strife, to pass as rapidly as may be, into the shades of oblivion. But wedded to a love of peace, as we are, by all the promptings of our soul—and as fully aware as any, we trust, of the horrors which follow in the train of war, this is, to us, a state of things which we regret to witness.

We have believed that God has deigned to bless our nation; that in her struggles for the freedom we enjoy, He was with us—that His hand led our armies through a struggle, fearful in magnitude, and against odds, which could have been counterbalanced only by that signal Providence which seemingly guided the councils, and led the armies of the Revolution victorious, in the fearful contest which eventuated in the establishment of our National Independence, and of the hope of freedom for the world.

It may he right, for us to forget all pertaining to that momentous struggle! It may be right, that the names of the more than spartan band, should be obliterated from the scroll of Fame, and that their memory should be blotted from the annuals (sic, for annals) of our country, and from the earth—that the past, and the present, should be separated by a chasm which not even thought can pass. But if it is right, then to us does it seem right, that the most signal providences of God, which have ever been manifested to any nation on earth, and the most manifest displays of His persevering, and fostering goodness, which any people have ever witnessed, should, also be effaced from human memory, and all that He has done for us, should be considered as valueless, and useless. Yes, we are free to confess that to our mind, forgetfulness of our country’s History—forgetfulness of the patriots be raised up, and the sufferings they endured for our good, in laying the foundation of our Freedom, and ingratitude to God, are one. And hence, we would never have those events forgotten, which give us to reflect on the heroism, patriotism, and suffering of our fathers, in the day of our country’s and freedom’s struggle—but WE WOULD HAVE THOSE events live, ever fresh in the memory of all; that they may be in us, the nurses of the lofty spirit which prompted them to do, and dare for the right!

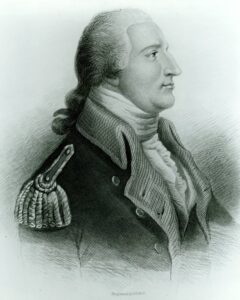

The past has thought, as we now write. And hence, the granite pile has gone up, that its summit might greet the sun in his coming, to usher in the day, which commemorates deeds, which, though disastrous in their immediate results, bore witness, nevertheless, to as noble heroism, and as lofty patriotism as characterized any act in that age of heroes. And if the sixth of September is to be permitted to pass, in forgetfulness, by us, of the deeds which it commemorates, far better would it be, that we raze the monumental column to the ground, and OBLITERATE FROM THE SPEAKING MARBLE THE NAMES OF THE EIGHTY-FOUR WHO WERE IMOLATED ON THE WORSE THAN VANDAL ALTAR OF FIENDISH CRUELTY, while a TRAITOR looked approvingly on, as a brutal fiend sheathed the sword of a surrendered and unarmed foeman in his defenceless breast.

True, the revolutionary struggle witnessed many a brighter, and happier scene for us, Than The Massacre At Fort Griswold, and scarcely any more disastrous, or dreadful—but, never did that struggle witness a more Gallant, Heroic, Or Devoted Band, Than That Which Against Fearful Odds, Stood Firm Till Hope Had Quenched Her Torch At Their Side, And Further Resistance And Madness Would Have Been Identified.

The following reprint, of a small pamphlet, written by one, who was an actor in the defence of Fort Griswold, and a witness of the massacre, subsequent to its surrender, is worthy of preservation. And we hope that, hereafter, the recurrence of the Sixth of September will be noticed by suitable demonstrations on the part of our citizens, in order that memory of the sacrifices of the past, may inspire coming ages, with a spirit which shall prompt them to cherish, with suitable gratitude, the liberty which was purchased at such fearful cost.

On the morning of the 6ih of September, 1784, twenty-four sail of the enemy’s shipping appeared to the westward of New London harbor. The enemy landed in two divisions, of about 800 men each, commanded by that infamous traitor to his country, Benedict Arnold, who headed the division that landed on the New London side, near Brown’s farms; the other division, commanded by Colonel Eyre, landed on Groton Point nearly opposite. I was first sergeant of Capt. Adam Shapley’s company of State troops, and was stationed with him at the time, with about twenty-three men, at Fort Trumbull, on the New London side. This was a mere breastwork or water battery, open from behind, and the enemy coming on us from that quarter, we spiked our cannon, and commenced a retreat across the river to Fort Griswold, in three boats. The enemy were so near that they overshot us with their muskets, and succeeded in capturing one boat with six men commanded by Josiah Smith, a private. They afterwards proceeded to New London and burnt the town. We were received by the garrison with enthusiasm, being considered experienced artillerists, whom they much needed, and we were immediately assigned our stations. The Fort was oblong square, with bastions at opposite angels (sic, for angles), the longest side fronting the river in a N. W. and S. E direction. Its walls were of stone, and were ten or twelve feet high on the lower side, and surrounded by a ditch. On the wall were pickets projecting over twelve feet; above this was a parapet with embrasures, and within, a platform for the cannon, and a step to mount upon to shoot over the parapet with small arms.

On the morning of the 6ih of September, 1784, twenty-four sail of the enemy’s shipping appeared to the westward of New London harbor. The enemy landed in two divisions, of about 800 men each, commanded by that infamous traitor to his country, Benedict Arnold, who headed the division that landed on the New London side, near Brown’s farms; the other division, commanded by Colonel Eyre, landed on Groton Point nearly opposite. I was first sergeant of Capt. Adam Shapley’s company of State troops, and was stationed with him at the time, with about twenty-three men, at Fort Trumbull, on the New London side. This was a mere breastwork or water battery, open from behind, and the enemy coming on us from that quarter, we spiked our cannon, and commenced a retreat across the river to Fort Griswold, in three boats. The enemy were so near that they overshot us with their muskets, and succeeded in capturing one boat with six men commanded by Josiah Smith, a private. They afterwards proceeded to New London and burnt the town. We were received by the garrison with enthusiasm, being considered experienced artillerists, whom they much needed, and we were immediately assigned our stations. The Fort was oblong square, with bastions at opposite angels (sic, for angles), the longest side fronting the river in a N. W. and S. E direction. Its walls were of stone, and were ten or twelve feet high on the lower side, and surrounded by a ditch. On the wall were pickets projecting over twelve feet; above this was a parapet with embrasures, and within, a platform for the cannon, and a step to mount upon to shoot over the parapet with small arms.

In the S. W. bastion was a flag-staff, and in the side near the opposite angle was the gate, in front of which was a triangular breastwork to protect the gate; and to the right of this was a redoubt, with a three pounder in it, which was about one hundred and twenty yards from the gate.

Between the fort and the river was another battery, with a covered way, but which could not be used in this attack, as the enemy appeared in a different quarter. The garrison, with the volunteers, consisted of about one hundred and sixty men. Soon after our arrival the enemy appeared in force in some woods about half a mile S. E. of the fort, from whence they sent a flag of truce, which was met by Capt. Shapley, demanding an unconditional surrender, threatening at the same time to storm the fort instantly, if the terms were not accepted.

A council of war was held, and it was the unanimous voice, that the garrison was unable to defend themselves against so superior a force. But a militia colonel who was then in the fort, and had a body of men in the immediate vicinity, said he would reinforce them with two or three hundred men in fifteen minutes, if they would hold out; Col. Ledyard agreed to send back a defiance, upon the most solemn assurance of immediate succer (sic, for succor). For this purpose, Col. — started, his men being then in sight; but he was no more seen, nor did he even attempt a diversion in our favor.

When the “answer to their demand had been returned by Capt Shapley, the enemy were soon in motion and marched within a short distance of the fort, where, dividing the column they rushed furiously and simultaneously to the assault of the S. W. bastion and the opposite side. They were however repulsed with great slaughter, their commander mortally wounded, and Major Montgomery, next in rank, killed, having thrust been (sic, for been thrust) through the body, while in the act of scaling the walls at the S. W. bastion, by Capt, Shapley. The command then devolved on Col. Beckwith, a refugee from New Jersey, who commanded a corpse (sic, for corps) of that description. The enemy rallied and returned to the attack with great vigor, but were received and repulsed with equal firmness. During the attack a shot cut the halyards of the flag, and it fell to the ground, but was instantly remounted on a pike pole.

This accident proved fatal to us, as the enemy supposing that it had been struck by its defenders, rallied again, and rushing again with redoubled impetuosity, carried the S. W. bastion by storm. Until this moment, our loss was trifling in number, being six or seven killed, and eighteen or twenty wounded. Never was a post more bravely defended, nor a garrison more barbarously butchered. We fought with all kinds of weapons, and at all places, with a courage that deserved a better fate. Many of the enemy were killed under the walls by simply throwing shot over on them and never would we have relinquished our arms, had we had the least idea that such a catastrophe would have followed.

To describe this scene, I must be permitted to go back a little in my narrative. I commanded an 18 pounder on the south side of the gate, and while in the act of sighting my gun a ball passed through the embrasure, struck me a little above the right ear, grazing the skull, and cutting off the veins which bled profusely. A handkerchief was tied around it and I continued at my duty.

Discovering some little time after, that a British soldier had broken a picket at the bastion on my left, and was forcing himself through the hole, while the men stationed there were gazing at the battle which raged opposite to them, and observing no officer in that direction, I jumped from the platform and ran to them, crying my brave fellows, the enemy are breaking in behind you, and raised my pike to despatch the intruder, when a ball struck my left arm at the elbow, and my pike fell to the ground. Nevertheless I grasped it with my right hand, and with the men who turned and fought manfully, clear[ed] the breach.

The enemy, however, soon after forced the S. W. bastion, where Capt. Shapley, Capt. Peter Richards, Lieut. Richard Chapman, and several other men of distinction, and volunteers, had fought with unconquerable courage, and were all either killed or mortally wounded, and sustained the brunt of every attack.

Colonel Ledyard, seeing the enemy within the fort gave orders to cease firing, and to throw down our arms as the fort had surrendered. We did so, but they continued firing upon us, crossed the fort and opened the gate, when they marched in, firing in platoons upon those who were retreating to the magazine and barrack rooms for safety. At this moment the renegade Colonel commanding, cried out, “Who commands this garrison?” Colonel Ledyard, who was standing near me, answered, “I did sir, but you do now,” at the same time stepping forwards himself. At this moment I perceived a soldier in the act of bayoneting me from behind. I turned suddenly round and grasped his bayonet, endeavoring to unship it, and knock off the thrust —but in vain. Having but one hand, he succeeded in forcing it into my right hip, above the joint, and just below the abdomen, and crushed me to the ground. The first person I saw afterwards was my brave commander, a corpse by my side, having been run through the body with his own sword, by the savage renegade. Never was a scene of more brutal wanton carnage witnessed, than now took place. The enemy were still firing on us by platoons in the barrack rooms, which they continued for some minutes, when they discovered they were in danger of being blown up, by communicating fire to the powder scattered at the mouth of the magazine, while delivering out cartriges (sic), nor did it then cease in the rooms for some minutes longer. All this time the bayonet was “freely used,” even on those [who] were helplessly wounded, and in the agonies of death. I recollect Captain William Seymour, a volunteer, from Hartford, had thirteen bayonet wounds, although his knee had previously been shattered by a ball, so much so that it was obliged to be amputated the next day.— But I need not mention particular cases. I have already said that we had six killed and eighteen wounded, previous to their storming our lines; eighty five were killed in all, thirty-five mortally and dangerously wounded, and forty taken prisoners to New York, most of them slightly hurt.

After the massacre they plundered us of every thing we had, and left us literally naked. When they commenced gathering us up, together with their own wounded, they put theirs under the shade of the platform, and exposed us to the sun, in front of the barracks where we remained over an hour. Those that could stand were then paraded, and ordered to the landing, while those that could not (of which I was one) were put into one of our ammunition wagons, and taken to the brow of the hill (which was very steep, and at least one hundred rods in descent) from whence it was permitted to run down by itself, but was arrested in its course, near the river, by an apple tree. The pain and anguish we all endured in this rapid descent, as the wagon jumped and jostled over rocks and holes, is inconceivable; and the jar in its arrest was like bursting the wires of life asunder, and caused us to shriek with almost supernatural force. Our cries were distinctly heard and noticed on the opposite side of the river (which is nearly a mile wide) amidst all the confusion which raged in burning and sacking the town. We remained in the wagon more than an hour before our humane conquerors hunted us up, when we were again paraded and laid on the beach, preparatory to embarkation. But by the interposition of Ebenezer Ledyard (brother to Col. L.) who humanely represented our deplorable situation and the impossibility of our being able to reach New York, thirty-five of us were paroled in the usual form. Being near the house of Ebenezer Avery, who was also one of our number, we were taken into it. Here we had not long remained, before a marauding party set fire to every room, evidently intending to burn us up with the house. Ebenezer Ledyard again interfered and obtained a sentinel to remain and guard us until the last of the enemy embarked, about 11 o’clock at night. None of our people came to us till near daylight the next morning, not knowing previous to that time, that the enemy had departed.

Such a night of distress and anguish was scarcely ever passed by mortal. Thirty-five of us were lying on the bare floor—stiff, mangled and wounded in every manner, exhausted with pain, fatigue and loss of blood, without clothes or any thing to cover us, trembling with cold and spasms of extreme anguish, without fire or light, parched with excrutiating (sic) thirst, not a wound dressed, nor a soul to administer to one of our wants, nor an assisting hand to turn us during these long tedious hours of the night; nothing but groans and unavailing signs were heard, and two of our number did not live to see the light of the morning, which brought with it some ministering angels to our relief. The first was in the person of Miss Fanny Ledyard, of Southold. L. I., then on a visit to her uncle, our murdered commander, who held to my lips a cup of warm chocolate, and soon after returned with wine and other refreshments, which revived us a little. For these kindnesses, she has never ceased to receive my most grateful thanks, and fervent prayers for her felicity.

The cruelty of our enemy cannot be conceived, and our renegado countrymen surpassed in this respect, if possible, our British foes. We were at least an hour after the battle, within a few steps of a pump in the garrison, well supplied with water, and, although we were suffering with thirst, they would not permit us to take a drop of it, nor give us any themselves. Some of our number who were not disabled from going to the pump, were repulsed with the bayonet, and not one drop did I taste after the action commenced, although begging for it after I was wounded, of all who came near me, until relieved by Miss Ledyard. We were a horrible sight at this time. Our own friends did not know us—even my own wife came into the room in search of me, and did not recognize me, and as I did not see her, she left the room to seek for me among the slain, who had been collected under a large elm tree near the house. It was with the utmost difficulty that many of them could be identified, and we were frequently called upon to assist their friends in distinguishing them, by remembering particular wounds, &c. Being myself taken out by two men for this purpose, I met my wife and brother, who, after my wounds were dressed by Dr. Downer from Preston, took me—not to my own home, for that was in ashes, as also every particle of my property, furniture and clothing— but to my brother’s where I lay eleven months as helpless as a child, and to this day feel the effects of it severely.

Such was the battle of Groton Heights; and such, as far as my imperfect manner and language can describe, a part of the sufferings which we endured. Never for a moment have I regretted the share I had in it; I would for an equal degree of honor, and the prosperity which has resulted to my country from the Revolution, be willing, if possible, to suffer it again. I regret very much, my not being able to be with my compatriots and co-veterans at the late celebration. Stephen Hempstead.

Capt. P. Richards, Lieut. Chapman, and several others were killed in the bastion; Capt. Shapley and others wounded. He died of his wounds in January following.

—New London Democrat, Sept. 12, 1846, p. 2. Transcribed by Eugene F. Gray. The text suffers from broken and worn type and misspellings, some of which I have corrected, some of which I have left intact, as well as the whimsical use of capital letters and italics in the introduction.